I was never a model. I was never interested. Yet, here was me again in a slouchy pose, this time against a construction barrier on Prince Street. If friends saw me, they would’ve teased me mercilessly. I didn’t mind. This was my natural stance that only seemed a great reanimation of a 1950’s Kerouac cool. Like breadcrumbs to a pigeon, a young man appeared before me with a camera. “Would you mind if I took your picture?” he asked.

“What took you so long?” I deadpanned. He laughed, his camera now in front of his face, one brow closing as the other arched, as the tdtdtdtdtd of his camera sounded off. I gave him more options, standing to face him directly, as my gaze moved in a slow drift across the sky, settling on the 1870 logo of a cast iron building. tdtdtdtd tdtdtdtd.

“You look great, like an ad in a magazine”, he said beaming. “Thank you.”

“You’re welcome”, I answered with a polite nod.” As he began to walk away, he turned back and said, “You’re the only person who didn’t ask me what the pictures were for or if I could send you some. Most people just end it at No.” His admission made me sad. But it got me thinking about the past, my past. I never said no.

I’ll have to go back some years for a person to understand my easy come easy go photography attitude. You see, back in the spring of a year in the late 1980’s, a woman approached me on Bleecker Street and asked if I’d like to be photographed by Richard Avedon for a potential job. The job was for Calvin Klein. I barely had heard of Avedon, but my fast reply answered before I even considered it, “Sure.” She took three polaroids of me on the street, took my number and said someone would be in touch. Someone was. Soon I was being test shot by Richard Avedon at his studio for a CK One spot. Later we chat over leftover chicken at a table where his most famous photograph of Marilyn Monroe hangs on the wall behind us. Her expression reveals the hint of a horror, as if fate has whispered in her ear that the crucifixion of her invention swirled in dark stars.

Avedon approved me for the job. I had a shoot date. I received a night before confirmation by phone (our sole mode of communication at that time) and low and behold the next morning a call came that Calvin Klein rejected me. Though a slight burn of a letdown flickered for a minute, I was well adjusted for a day of anonymous me. This was a time before every person felt they had a brand to grow. Decades before walking down the street counted as a career appearance. This was a beautiful and exciting blip in the history of photography. I was a willing participant, always ready for anyone with a camera. In salacious terms I was the town whore. Can I take your picture? was the question often put to me, and my lightening reply to anyone was “Yes.” Yet mine was one of passionate curiosity within the process. With each photograph I gained knowledge and experience. I became smarter as I made lifelong friendships with a windfall of these acutely focused photography devotees armed with cameras. Their skin and breath excreted the scent of film. Their minds mimicked it. Photographers are smart because they exist in surveillance mode.

I live a few blocks off Times Square. I pass through this nexus of photographic hysteria often. It is a curious phenomenon to witness nearly every human being from every imaginable place on earth each taking pictures. Most are taking pictures with iPhones. But there is a fair amount of people armed with digital cameras. I sometimes spy the sort of pictures people are taking… a pulsating sign, a passing fire engine and a woman with her finger indicating the 2025 sign atop One Times Square. I see a clique of teen girls with each straightened hair, flared jeans, and small tight stretchy tops. They shiver in sub-zero weather but are determined to be photographed in seductive poses in Times Square. I don’t understand any of it.

Photography in its blossoming accessibility circa 1840’s became the technology that first served the very rich. It was expensive to produce. The gilded folks had the money and wanted fast portraits for the bragging rights of access to this wholly magical technology. Sadly, many portrait painters of that time became the ancestors of our Starbucks Baristas. Another interesting transformation took place in the recent 30 years, the cycle of technology repeated itself yet again, first for the rich and then for everyone else. Along the way, the “sell” of it and the common feeling was the more people who have access the greater the outcome. It didn’t quite work out that way. The outcome has led to a poisonous glut of megabytes, files, storage drives and much filled with the same unspectacular images. The landfill of technology is poisoning the cosmos. As if this isn’t enough, the “backing up” of everything has become the necessary life insurance that will never pay. What ever will you do if you lose the ten thousand duplicates of playing beer pong in 2013? Cynicism aside, whose task will it be to one day have to delete all of this, the microplastics of art. The succession of snaps provides a battery of duplicates, atomic like fissures that flatten the landscape. Taking your time with a 12-frame roll of film beautifully wound into a Rolleiflex won’t guarantee genius, but it doesn’t add more noise to a world bleeding mediocrity from its eyes and ears. Yes, I know. There is no going back.

A “great“photograph has indoctrinated the faithful consumers whose first try at the medium was an iPhone. “Great” now means an absurdly granular clarity of megapixels no one even needs. Cameras have become microscopes, and it should come as little wonder why everyone, except the under 20 crowd, looks sort of old and lousy with these devices. Hail Apple marketing. The new strive shares no relationship to the definitions of great in the previous hundred years when a relative few people brought a dynamic style and bursts of individualism, armed with imperfect machines hanging around their necks and gripped by their hands. Now, taking the photograph has become the droll means to an end, the location as star has supplanted the technology. People want access to a place, a punch list of places spread across the Globe, and they want themselves melded into the history of that pop-majestic place. The motivation lies in a chaste hunger for garnering attention for oneself. People pine for likes on a global scale from complete strangers who can respond, comment, contact a person, and perhaps develop an unhealthy obsession based on what a person is posting. I’ve just described the business plan of Only Fans. Irony abounds, the peddle everything cultural moment cruelly sharpens suspicion for a friendly guy on the street who asks to take a person’s picture. I ask, why villainize him? What could go wrong that already hasn’t by one’s own fruition online, or in life?

Bruce Weber leads me into the dusty backyard of crabgrass at a house I rented out east. The sky is overcast. “That’s good,” said Bruce. I stand facing him, hands deep in pockets of loose white denim jeans, barefoot and with a slight bit of wonder in my expression. He wears denim, a linen shirt and scarf and a colorfully patterned bandana over his head. He snaps a half dozen pictures of me. He doesn’t talk about cameras. He grips one with a wooden handle. It looks so deeply serious. It is a 6 x 9 format. Later we go inside. I sit on the kitchen counter. He says nothing but amps up as he sees me framed by homemaker cute window curtains. I lean into my propped fist under my chin. He moves into position. A few snaps sound.

These are portraits of me at a time, age, and to a place I can never return. This is me by a Bruce Weber that I hadn’t really known so well. Through this quiet moment Bruce became a friend. He educated me through books, art, ideas and humor. He introduced me to a lot of things that I am passionate about today. He was the first person to tell me I am a writer. He introduced me to Marianne Faithful, Paul Morrisey and many other interesting pop culture figures. Bruce is a rousing friend. I gained a lot more from Bruce than his beautiful photographs of me. I am grateful to him for it all.

Classic photography presents the most convincing evidence of who you are and who you wish to be. It is also a competition of sorts between allies on two sides of the camera both vying for the same outcome for different reasons. It is an exercise as much as it is a magical fusion between two people. A photograph printed on paper gives the subject a chance to find themselves. Even for a supermodel covered, painted, coifed and presented, there in the microdots of print lies the DNA of their true selves. Unbeknownst to every viewer it is the real person that gives the image its muscle. Being photographed is almost like having blood drawn. A regeneration takes place. It can feel sexual.

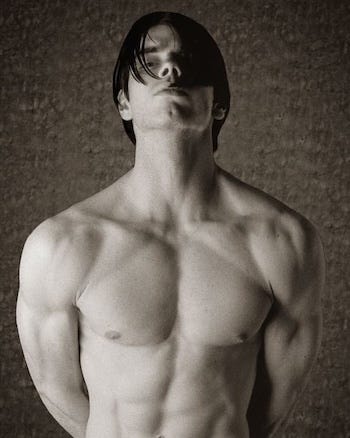

Joe Lalli said he’d be at my place at 10:00 A.M. He is on time. As he loads the 120 film into his Yashica camera, I kick back on a futon, shirtless wearing Fruit of The Loom white briefs. I light a cigarette. No words are spoken, just soft faint sounds of singular clicks between the roll being wound one frame ahead. Joe photographed me many times over the years and with each time, we understood ourselves and each other better. He projected an idea on to me and it became the illusion of my authentic identity every time. Yet, the real me made an appearance in each photograph. As masked as it may have first seemed, I was always there. Sadly, Joe is gone now, and his photographs of me have the added weight of all the good that has now passed.

People presume it is a vanity that drives one to the thrill of being photographed. None of that has ever been my motivation. Duane Michals once said of me, “If you want to cheer Michael up, take his picture.” He makes a point. Staring into a lens and then a printed image of oneself hones a sense of self through examination. Yet the process also returns a gaze of chronic mystery. In perfect pairings of photographer and subject, the subject doesn’t see what the photographer or the world sees. It is a multi-dimensional mirror. The more you are photographed, the more you study the images, the closer you get to discovering a new piece of yourself. How the world reacts to it is stripped to a naked wonder for the subject. You soon realize how others see you even when you don’t at all see things as they do. There’s a gift in this, a detangling of knots within identity.

Duane Michals tells me to lean back on a wall of his apartment where new spring light has settled. I’m shirtless. He has placed flower petals across my chest and on my shoulders. I am wearing a crown made of paper. He has cast me as a wounded prince. There are no assistants, not many words are spoken. I don’t yet know him very well. I comply with the artist’s vision even if I’m uncertain what is happening within him. It’s trust. He sees it and I believe in what I can’t see that’s happening inside of him. It’s a creative form of Catholicism. The results are beautiful, simple, and above all unique. He doesn’t talk technology. He doesn’t care about cameras. He doesn’t have a favorite piece of equipment or insists on really anything mechanically. He is shooting with a simple 35mm camera, horizontally (always). He is driven entirely by the idea within. He is by all measures, an original. He is an artist. He is a true friend. We have worked together many times over the years. One night at dinner, he also introduced me to the Pharaoh of all photographers, Robert Frank. What an experience, what a memory.

There is a fair amount of me in every photograph anyone has taken of me, woven with a scrap book of secrecy, insecurity, and maybe a bit of shame of who I wish to be. Some images represent me eager to please the photographer who has projected a hero or masculine archetype onto me. Others are lucky accidents where I am being me, doing the right thing just as the photographer is hitting the shutter at just the right time. There also exists in time parts of me in some of the images that have been forever lost. I no longer possess all the traits I once took for granted. It’s a process that tracks alongside the natural order of growth, aging, all that so easily had been to what is not any longer. Yet, through it all, I take solace knowing that I was once a crowned Prince to an imagined kingdom wished into an eternity. With a gust of youthful spirit, I rule gently over my soul from the chambers of an aging heart. I dream in photographs.

photographs in order by: Self, Hans Fahrmeyer, Anonymous, two by Bruce Weber, two by Joe Lalli, two by Duane Michals

Michael, one of your best. Laurence Olivier said that Marilyn Monroe always stalled getting onto the set on The Prince and the Showgirl because "She didn't want to act, she just wanted to be photographed." This piece brings us closer to what Olivier meant.

You should save "I never said no" for your tombstone.

Ah, now things come slowly into view. Become more understood. Love seeing and learning about this time of your life through your excellent writing. A true creative in all ways. The best thing to be.